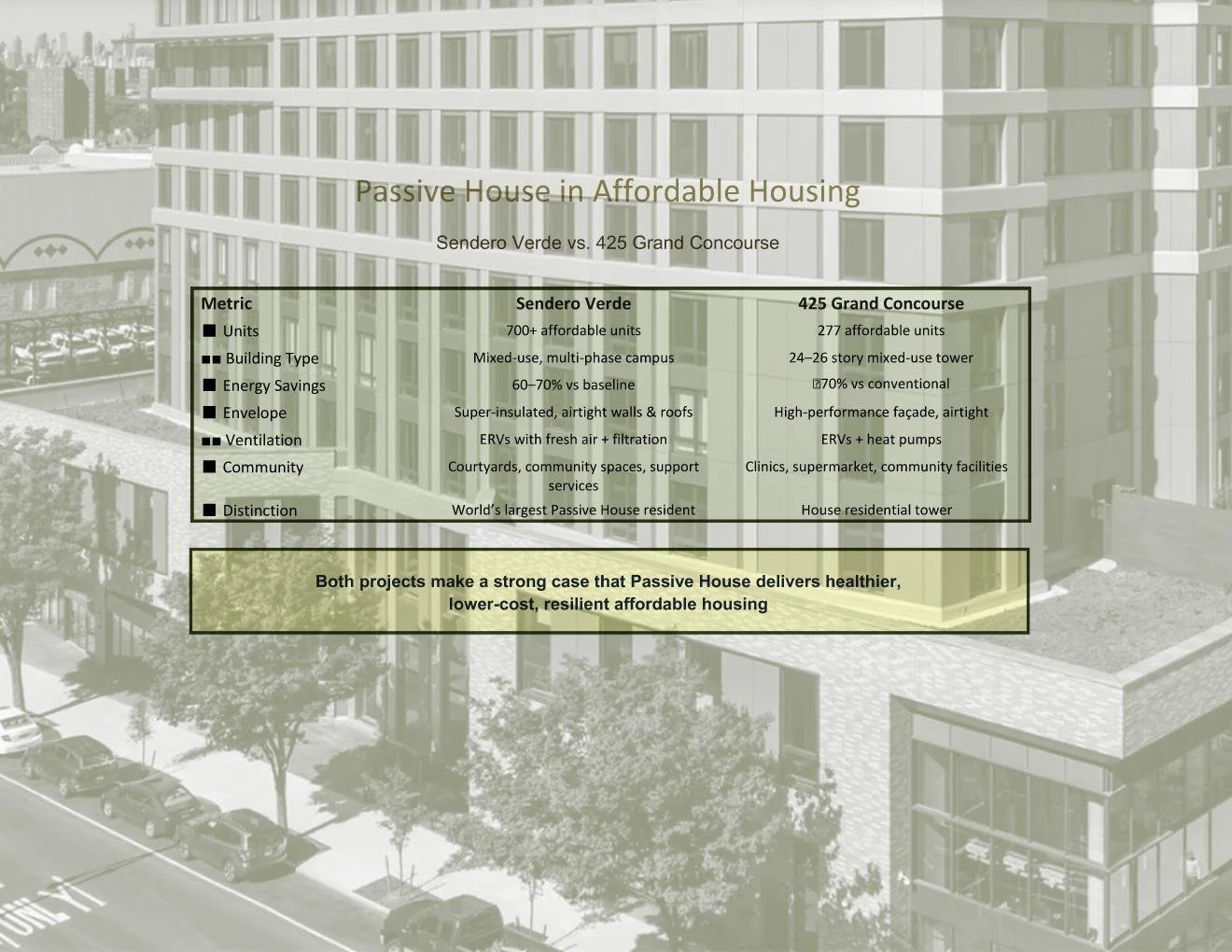

Passive House is often talked about in the context of high-end, single-family homes or flagship sustainability projects. But two recent New York developments — Sendero Verde in East Harlem and 425 Grand Concourse in the Bronx — make a practical, hard-to-ignore case that the Passive House approach is exceptionally well suited to affordable housing. Below I summarize each project and then pull out the lessons that matter to developers, housing authorities, and policymakers.

Quick project snapshots

Sendero Verde (East Harlem)

A fully affordable, mixed-use complex designed to Passive House standards, Sendero Verde is being delivered in phases and is described by the design team and city agencies as the largest Passive House residential development in the world, delivering roughly 700+ affordable units and a range of community spaces. Its design explicitly pairs high-performance envelope strategies with generous shared open space and community services. Handel Architects

Sendero Verde by Handel Architects

425 Grand Concourse (Mott Haven, Bronx)

A 24–26 story mixed-use, mixed-income tower designed to PHIUS/Passive House performance, 425 Grand Concourse includes hundreds of affordable units alongside retail, medical, and community uses. The project was pursued in part as a demonstration that tall, dense affordable housing can meet Passive House/PHIUS performance and the project team reports very large energy reductions compared with conventional construction (the team cites performance reductions in the range that Passive House projects typically hit). The building uses a tight envelope, energy-recovery ventilation, heat-pump HVAC strategies and other integrated systems to lower energy demand and improve indoor comfort. Dattner Architects

What these two projects show about Passive House + affordable housing

1) Big energy savings translate to real rent/operating benefits

Both projects prioritize a super-insulated, airtight envelope and balanced mechanical ventilation. That means dramatically lower heating and cooling loads — which translates directly to lower utility bills for residents and lower ongoing operating costs for owners/PHAs. For developments where either tenants pay utilities or owners operate under tight budgets, saving 30–70% of energy (depending on climate and systems) is not abstract — it’s cash that can be reinvested into services, maintenance, or keeping rents affordable. NYSERDA

2) Better comfort and health — measurable and immediate

Passive House’s required ventilation strategy (ERV/HRV with filtration and continuous fresh air) improves indoor air quality and reduces drafts, cold surfaces, and temperature swings. For low-income households — who disproportionately include people with respiratory vulnerabilities or limited means to control their micro-environment — those health and comfort wins matter. Both Sendero Verde and 425 Grand Concourse emphasized IAQ and occupant comfort as explicit project goals alongside energy savings. NYHC

3) Resilience and system simplicity reduce long-term risk

High-performance envelopes reduce the amount of active heating/cooling equipment required; internal gains in dense multi-family buildings often mean less extreme heating demand. That helps buildings stay habitable longer during outages and reduces dependency on complicated, failure-prone systems. In affordable housing, reducing maintenance burden and single-point mechanical risks can lower lifecycle costs and avoid tenant disruptions. 425 Grand Concourse in particular was designed with resilience strategies and system simplicity in mind. NYSERDA

4) Passive House is scalable — from mid-rise to tall, mixed-use buildings

A common myth is that Passive House only “works” for small, detached houses. Sendero Verde and 425 Grand Concourse disprove that: the strategies are applicable at scale. The careful detailing, panelization possibilities, and predictable energy models make Passive House a replicable approach for large affordable projects, especially when design teams integrate the standard early in procurement and budgeting. Handel Architects

5) Policy and procurement can make or break adoption

Both projects grew out of city calls for proposals and programs that prioritized sustainability and affordability. That’s not a coincidence: when municipal RFPs explicitly reward verified performance or require Passive House/PHIUS targets, developers take the technical and budgetary steps needed to deliver. These projects are useful demonstrations for policymakers that incentives + clear performance targets yield bankable, replicable outcomes. NYC Government

Trade-offs and realities (so the praise is practical, not pie-in-the-sky)

Upfront cost discipline matters. Passive House can increase initial construction costs if the design team treats the envelope and mechanical approach as add-ons. But when teams design to the standard from the start (and seek economies of scale, prefab elements, or integrated procurement), lifecycle cost savings and lower operating budgets usually justify the premium. Projects like Sendero Verde built the performance requirement into procurement, which helps control costs. Handel Architects

Skilled teams are essential. Achieving airtightness, thermal continuity, and balanced ventilation on large buildings requires contractors and trades comfortable with high-performance detailing. Training and early QA/QC on site are necessary investments.

Monitoring and commissioning pay off. Long-term energy claims only hold if systems are commissioned and occupants are supported (tenant education, simple controls). Both projects highlight thorough commissioning and system integration as critical steps.

Bottom line — why cities should lean in

Sendero Verde and 425 Grand Concourse are more than architectural wins; they’re proof that Passive House principles deliver measurable benefits for affordable housing: lower utility burden, healthier indoor environments, more resilient buildings, and a scalable path to low-carbon housing stock. For cities that need to deliver housing at scale while meeting climate goals and protecting low-income residents from energy cost shocks, these projects provide compelling, evidence-backed models to follow. If the goal is housing that’s economical to operate, healthier to live in, and future-proofed against climate risk — Passive House belongs in the toolkit.